What is waterfalling the sprint?

I recently received a question from a former student that expresses a struggle that a lot of Agile teams deal with shortly after transitioning from waterfall patterns in their sprint:

I have been a part of scrum teams in various forms. There seems to be a struggle with allowing time for testing to be done during the sprint. For example, in a three-week sprint is there a recommended cutoff time for all development to be done such as after two weeks or is it more fluid? What we seem to happening at my current workplace is testers are receiving things late in the Sprint which crunches them at the very end. Do you have any mitigation strategies so that we’re not throttling the testers at the end?

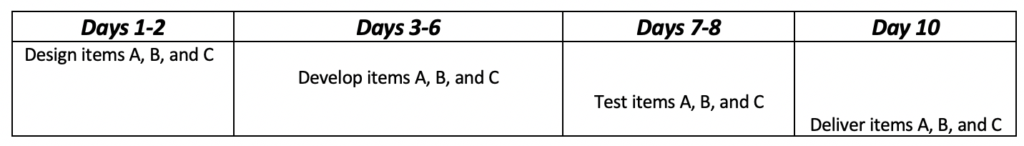

The phrase that describes this pattern is “waterfalling the sprint.” The team appears to be planning and executing sprints, but inside of the sprint timebox they still handle all of the phases of work as discrete, siloed steps. A team that’s waterfalling their sprints might think they’re going to do something that looks like this while trying to build backlog Items ‘A,’ ‘B,’ and ‘C’ in a 10-day sprint:

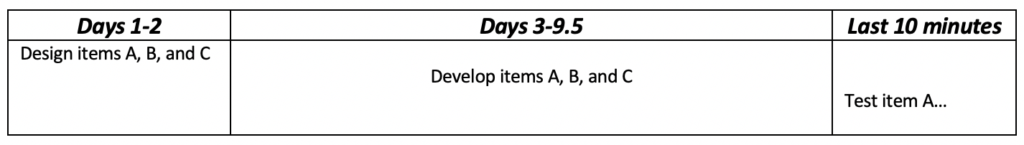

Well…that’s the plan, anyway. Instead what typically happens is this:

Why is waterfalling the sprint a problem?

Throughout the sprint, people thought of as ‘testers’ are sitting around, while people thought of as ‘developers’ build all three items. Development takes longer than expected, leaving only minutes at the end of the sprint for validation and delivery tasks, most which won’t happen. The net result is that none of the items are fully tested, let alone delivered to a production environment. Now, any remaining testing and delivery tasks will roll over to the next iteration, while the ‘developers’ tackle new backlog items. From this point on, the team is in a continual pattern of bouncing between starting new work and fixing newly discovered bugs in old work that they thought was done already.

There are a bunch of background conditions that lead to waterfalling the sprint, which are also issues with team health in their own right. Some of the most common are:

- Not enough backlog refinement. Where backlog refinement is missing or ineffective, teams commit to product backlog items that aren’t understood well. Then, they spend precious work time during the sprint negotiating the meaning of items after the fact, often discovering those items are far more complicated than they were expecting. And now there’s no way for them to complete their mini-waterfall plan in the remaining days of the sprint.

- Thinking of people as jobs, instead of team members. Scrum teams are supposed to be cross-functional, with the team being mutually accountable for all aspects of ‘how’ within a sprint. But sometimes legacy patterns of single-function workers persist that derail this key aspect of a team’s ability to self-organize. For example, when team members think in terms like, “I am a developer and that person is the tester,” when instead the more functional pattern is, “We are both responsible for all the development and testing.” This leads to the kind of ‘my tasks are waiting on your tasks’ behaviors that encourage the within-sprint waterfall issue, and probably means we don’t have time to do the kinds of cross-training and pairing/swarming collaboration that lead more value delivery over time.

- Focusing on output instead of outcome. If the culture surrounding the team is focusing awareness on the wrong indicators, that can be a further incentive to waterfall the sprint, and claim ‘credit’ for partially done backlog items. For example, where teams are relentlessly valued on speed of process measures like velocity, rather than tangible business objectives (revenue, operations cost, usership, etc.), that attention teaches teams to prioritize ‘being busy’ over delivering. This can especially be seen with Scrum teams that are waterfalling their sprints whenever they begin to split backlog items along quality boundaries: “We didn’t get this item tested during the sprint, so we’ll split into the development part, which we claim velocity for, and the testing part, which we’ll do next sprint.” The elements of the backlog item that being called ‘done’ don’t have any business value because they can’t be shipped yet, but the team looks better on the metric that’s being used to reward or punish teams. This behavior also robs teams of a critical bit of feedback that would tell them that they’re planning unrealistically.

How can you help teams stop?

So how can we help teams stop waterfalling their sprints? Most of the time, I recommend teams start with trying two new patterns:

- Commit to less backlog items in a sprint until you figure out what a realistic commitment is. ‘Realistic’ here meaning “the number of things we can build that completely meets our definition of done by the end of the sprint.” There will typically be pushback from stakeholders outside of the team who perceive the productivity of the team to suddenly drop significantly, but this can overcome by coaching them to realize that the team’s current productivity is actually near zero in terms of what matters most: tangible business outcomes.

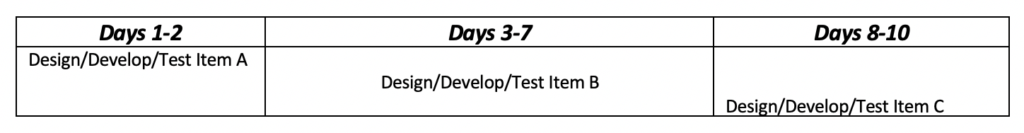

- Emphasize finishing backlog items over starting them. This means replacing their prior work pattern with something that looks more like:

This pattern reinforces that the team collectively owns all of the work in the sprint (especially if they’re also willing to trying pairing/mobbing/swarming behaviors), and helps show that what matters within the sprint is ‘done items’, not busy-ness. And, if nothing else, even if they run out of time before they finish ‘C,’ at least ‘A’ and ‘B’ are complete to a point of actual value!

See NextUp Solutions’ upcoming courses!

You Might Also Like

Is Your Team’s Sprint Planning Broken?

Scrum is a framework that operates in a rhythmic cadence called “sprints,” which are fixed...

The Three Inspect and Adapt Loops in Scrum

What’s Empirical Process Control and Why Do We Use It? Defined process control (DPC) methods...